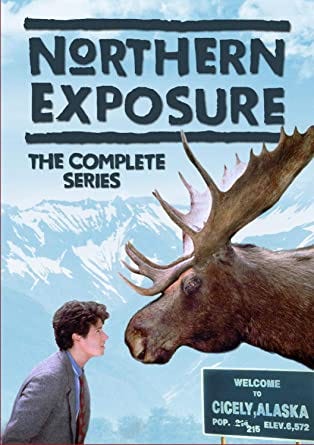

Thirty years ago, “Northern Exposure” spoke to my soul. It still does.

There are certain pieces of music that make my shoulders relax, which is no small feat. (A physical therapist of mine once held up her fist, held so tightly that the tendons in her forearm were visible, and said, “This is how you walk around all day long.”) Most of these pieces of music are by Rufus Wainwright, but many of them are also television theme songs, and one of them is the theme to Northern Exposure.

I have absolutely no idea how to describe music in actual musical terms, but here goes: there’s a subtle drumbeat intro, then a bass line kicks in, and only a couple measures in does the zydeco melody line come in. It moves along quickly, theme, counter-theme, and then it returns to the bass line only, ending on the drums. It’s whimsical without being sweet, beat-heavy and danceable. Perhaps the only justice to it that I can really do is that I’m listening to it now, and my shoulders are relaxed.

Thirty years ago, Northern Exposure debuted on a Thursday night, July 12, 1990, as a midseason replacement show on CBS. Its first season would only run for eight episodes, and I’m not sure I caught any of them (particularly as I don’t remember the show airing on Thursdays; I only remember it as a Monday night staple). In the summer of 1990 I would have been in high school, trapped on my parents’ farm, working for our farmer’s market stand business. If I wanted to see any television at night, I had to sneak away from whatever work I was supposed to be doing, picking raspberries or beans or sweet corn or whatever, and watch it in my brother’s room where I had a chance of escaping notice.

The plot device of the series is the fish out of water scenario. A doctor trained at Columbia University in New York City accepts the help of the state of Alaska in paying off his medical school bills, in exchange for practicing medicine there for four years. The doctor in question is Dr. Joel Fleischman, son of Herb and Nadine Fleischman of Queens, and played by Rob Morrow. Once in Alaska, Joel is appalled to find out that he will not be working in the (barely acceptable) urban area of Anchorage, but rather is pledged to spend his time in the small-town community of Cicely.

Throughout the pilot Joel is introduced to one unlikely town resident after another: Ed (Darren E. Burrows), a young man tasked with picking him up from the bus stop in the middle of nowhere to deliver him to Maurice Minnifield (Barry Corbin), former astronaut and owner of most of the land around Cicely, who dreams of making the town the “Alaskan Riviera” and alludes to its founding, nearly one hundred years prior, by two women who (according to the conservative Maurice) were just good friends, “rumors notwithstanding.” Eventually Joel sees what is meant to be his office, little more than a clapboard shack, where a Tlingit woman named Marilyn Whirlwind (Elaine Miles) announces “I’m here for the job,” even though Joel assures her he’s not staying and there is no job. Marilyn, like pretty much everyone else in town, mostly treats Joel’s protestations with polite indifference, and in one of the next scenes, we see Joel screaming into a public payphone at the town’s most popular gathering place, a tavern named The Brick, begging his fiancée Elaine to dig out his contract and find him a way out of Cicely. Of course she cannot: Joel is in Cicely to stay.

There were so many things to love in this program, not least the fact that it felt like it had been made to appeal specifically to me. Rob Morrow couldn’t have been more adorable as Joel, with his New York accent and smarts, a world away from my clique-ish Midwestern high school ruled by jocks and rich girls. I was only sixteen, but a lifelong attraction to smart, anxious, dark-haired, wire-rim-glasses-wearing men was already asserting itself. And let’s not forget one of the show’s other main characters: air taxi owner Maggie O’Connell, played by Janine Turner, who was alternately annoyed by and massively attracted to Joel throughout the show’s six seasons (although Morrow left the show midway through its sixth season). Turner was a gorgeous woman, even dressed in 90s fashion that leaned heavily to utilitarian canvas and flannel shirts over mom jeans and comfortable floral dresses (remember a time when a woman could wear grunge and still be considered attractive?), but perhaps most importantly, she had short hair. Very few women on broadcast television, in the 1990s or now, have a pixie cut and are still considered sexy.

The chemistry between Joel and Maggie was mesmerizing, but the real love story in Northern Exposure was the one played out within the entire community. Like a town of misfit toys, everyone had their quirk: Ed was also an avid movie fan and aspiring filmmaker; Chris Stevens (played by lean and rangy and oh-so-attractive John Corbett) was the town’s radio DJ, ex-con, and resident quoter of philosophy; young Shelly Tambo (Cynthia Geary) came to Cicely as beauty pageant-winner Miss Northwest Passage, on the arm of Maurice, but eventually shacked up with The Brick’s owner Holling Vincoeur (John Cullum), forty+ years her senior. The show had depth: it also featured septuagenarian actress Peg Phillips as irascible Ruth-Anne Miller, who ran the general store, and offered guest stars from Adam Arkin to Richard Cummings Jr. to Anthony Edwards.

So, within its population of 800 or so, Cicely featured a doctor from New York who viscerally missed his bagels; an independent female pilot with short hair and witty sarcasm ever at the ready; an astronaut; a cinephile who studied both Steven Spielberg and Woody Allen; and a radio announcer who introduced me to names like Jung and Thoreau and Kierkegaard. I hadn’t heard any of these names in my highly rated suburban high school. I didn’t know any people like this. I watched the show religiously on Monday nights for the eight series it ran, and I dreamed of one day finding my own Cicely, filled with simultaneously rugged and intellectual types, all of whom — and this is the important part — were so accepting of one another’s individualities that they largely didn’t even bother noticing them as anything special.

It’s time for me to re-watch the entire series (although I do watch one of the show’s holiday episodes, “Seoul Mates,” every December), as some of the overall storylines have faded from my memory, but one episode that I will never forget was season three’s “Burning Down the House.” In this episode, in the middle of the show’s run, when it had really found its stride, Chris is building a giant catapult to fling a cow in a performance art experiment to “create a moment.” (Yes, Joel registers a complaint on behalf of all of us, that this will most likely cause the cow some distress; how I loved him then and still do.) When film buff Ed points out that such a moment had already been created in a Monty Python movie, Chris sinks into despair and gives up the idea. Maggie, meanwhile, is having her own problems: her mother is visiting from her wealthy hometown, Grosse Pointe in Michigan, to let her know that she and Maggie’s father are getting a divorce, which bothers Maggie more than she wants to admit. Her mother ends her visit in spectacular fashion, by burning down Maggie’s house, and only when Maggie is wandering through the remains of her home does Chris rouse himself to visit her…and find the object he really wants to fling.

Yeah, episode synopses really don’t do justice to Northern Exposure.

I remember that episode because I still remember how I felt when I watched it. When Chris “created his moment,” at the show’s end, my soul soared just like the object he was flinging (without really crashing back to earth). I felt so full of emotion and hope and excitement, all somewhat foreign feelings in my high-school and farm-kid experiences, that I just needed to TALK about it with someone. So I called up my friend Leanne, someone else who lived in my small town but always had a flavor of the urban about her, what with her Doc Martens and her closet full of army surplus items mingling with those from Urban Outfitters, and all we screamed at each other at first was “Did you just watch Northern Exposure?” What we said after that was unimportant. But we both recognized that something in the show spoke to our desire to be different, and to be accepted for being different. That’s what we wanted in a community.

I’m still waiting to find that in a real community, truthfully, but I refuse to lose hope. Until I find my own Cicely, I’ll just be thankful that for six years and 110 episodes, Northern Exposure was my community.

Sarah Cords is the author of Bingeworthy British Television: The Best Brit TV You Can’t Stop Watching. Fellow curmudgeons welcome at citizenreader.com.